Contents

This stage of the case study provides the following information.

- The Personal History sets out what is happening for Don and Madge.

- Values and Ethics – Relating to: Ageism and the focus on pathology; Active ageing and the risk of exclusion

- Law and policy – Relating to: Active ageing and wellbeing; Ageing in place

- Knowledge, Evidence and Good Practice – Relating to: Support networks and ageing; Gender and ageing; Religion, spirituality and ageing

- Skills – Relating to gathering biographical and background information

- Activities – Relating to: Housing; Assessment; Key Information; Self reflection

- Additional resources – Relating to different experiences of ageing.

Personal History

Don and Madge Cooper have been married for 55 years and live with their dog Sprocket, in a 3 bed semi-detached, owner-occupied house on the edge of a market town. They have lived there for over 40 years and are very attached to their home and local community.

Don (81) retired at 65, after many years working in locomotive engineering, with his strength and overall health already affected by osteoarthritis. Before retirement Madge (77) worked as a school dinner and playground assistant at a local primary school. The couple receive a state pension and Don has a modest occupational pension. Madge has no separate, private pension but they have some ‘rainy day’ savings (around £25,000) and premium bonds (£5,000).

The couple have no children which is a source of sadness to them both, especially to Madge who had always hoped for a big family. Madge had several miscarriages and after failed medical treatment to try and help her to bring a baby to full term, they decided to stop treatment and accept that they would not have children. They did not consider adopting a child.

Madge and Don are close to their nephew (Madge’s late sister’s son), Charlie, who lives over 100 miles away. Charlie is married with school age children and works long hours as a self-employed builder. He keeps in regular telephone contact with Madge and Don and tries to visit them every few weeks. Don and Madge often stay with Charlie and his family for a week in the summer and for a long weekend around Christmas. Don had a much older widowed sister who lived in a care home in Scotland but she died some years ago.

The couple are members of the local Methodist Church where Madge used to help with Sunday School. Madge in particular has a large network of friends and for many years has been an active member of the Women’s Institute (WI). She enjoys cooking, gardening and growing her own vegetables and belongs to a local gardening group. She is also a volunteer helping children with their reading at the school where she worked.

Don maintains a strong interest in engineering. Throughout his life he has restored and exhibited small steam engines and has a large garden shed and workshop. He is gradually doing less in the workshop but still enjoys his hobby and is connected to steam enthusiasts around the country. He had to give up driving and no longer goes to big national shows but he is in e-mail and Skype contact with some long-standing associates.

Madge has always had good health. In her forties she learned to drive and has driven ever since. She feels that this is crucial for her independence and for enabling Don to get to appointments and steam engine events. Madge provides quite a lot of practical support to Don and sees this as part of her role as his wife. She worries about Don and realises that his health is likely to deteriorate.

Don is an enthusiastic wine maker and they both enjoy a glass of wine with their evening meal.

Values and Ethics

Ageism and the focus on pathology

Madge and Don are drawing on the strengths and skills they have developed throughout their lives to manage the challenges of ageing, to pursue the activities they find fulfilling and to contribute to their community. In this they are typical of many older people and contrast with the negative stereotypes of ageing that permeate society.

Practitioners working with frail older people with complex needs are often immersed in the vulnerabilities and problems of later life. As a consequence they are at particular risk of developing ageist attitudes and negative and distorted views of old age. For practitioners to work in a sensitive and empowering way with older people, an understanding of older people as individuals with knowledge, skills, activities and relationships which enrich their daily lives is essential. Ageing is an inevitable part of human experience, so empowering practice also demands a willingness to engage reflexively with our own ageing, our assumptions, hopes and fears, and how these are shaped by our encounters with older people (Richards et al., 2007).

For many people late life is, by comparison with other life stages, a time of happiness and contentment. To find out more watch this Ted talk by psychologist Laura Carstensen from Stanford University.

Active ageing and the risk of exclusion

Madge and Don are examples of active ageing, but what will happen if their health deteriorates and they no longer participate in their many activities and are dependent on others to fulfil their basic needs? Will they become just passive recipients of care?

Critiques of the concept of active ageing reveal underlying tensions. In particular, active ageing aligns with the aspirations and behaviour of many Third Age people, but seems less relevant to life in the Fourth Age. Does this mean that the concept of active ageing marginalises the most frail and vulnerable older people? Findings from research into the perceptions and experiences of frail older people receiving care and support reveal that this life stage is often far from passive. Indeed people may expend immense physical, mental and emotional effort as they attempt to manage significant change and life events in a way that maintains their identity and dignity ( Lloyd et al 2014a). It is therefore essential that the idea of active ageing incorporates agency as exercised by frail older people. Enhancing and supporting agency for the most vulnerable older people is not only consistent with social work values but of vital importance to wellbeing in late life.

A wide range of socio-economic factors, such as income, housing, and education, are linked to inequalities in health across the life span. Active ageing, as defined by the World Health Organisation, is dependent on access to opportunities and resources. However, in the context of economic austerity, the responsibility for active ageing is shifted to individuals and communities. As a consequence inequality and social exclusion amongst the most disadvantaged individuals and communities is likely to increase (Lloyd et al., 2014b).

References

- Lloyd, L., Calnan, M., Cameron, A., Seymour, J., & Smith R. (2014a), ‘Identity in the fourth age: Perseverance, adaptation and maintaining dignity’, Ageing and Society, 34(1):1-19

- Lloyd, L., Tanner, D., Milne, A., Ray, M., Richards, S., Sullivan, M.P., Beech, C. and Phillips, J. (2014b) ‘Look after yourself: active ageing, individual responsibility and the decline of social work with older people in the UK’, European Journal of Social Work, 17/3: 322-335

- Richards, S., Donovan, S., Victor, C. and Ross, F. (2007) ‘Standing secure amidst a falling world? Practitioner understandings of old age in responses to a case vignette’, Journal of Interprofessional Care, 21(3):335 – 349.

Law and Policy

a) active ageing and wellbeing

Don and Madge have made a successful transition from paid employment to retirement and take personal responsibility for their own wellbeing. They engage in a wide range of activities and contribute to their local community. Although they have few family members, their friendship networks and Don’s IT skills provide a buffer against social isolation. Together they are managing Don’s deteriorating osteoarthritis. Gardening keeps Madge physically active and her fresh vegetables contribute to a healthy diet.

Don and Madge are examples of active ageing. Active ageing, is not just an individual lifestyle choice, but a concept which is central to global and national policy responses to population ageing. It has been defined as:

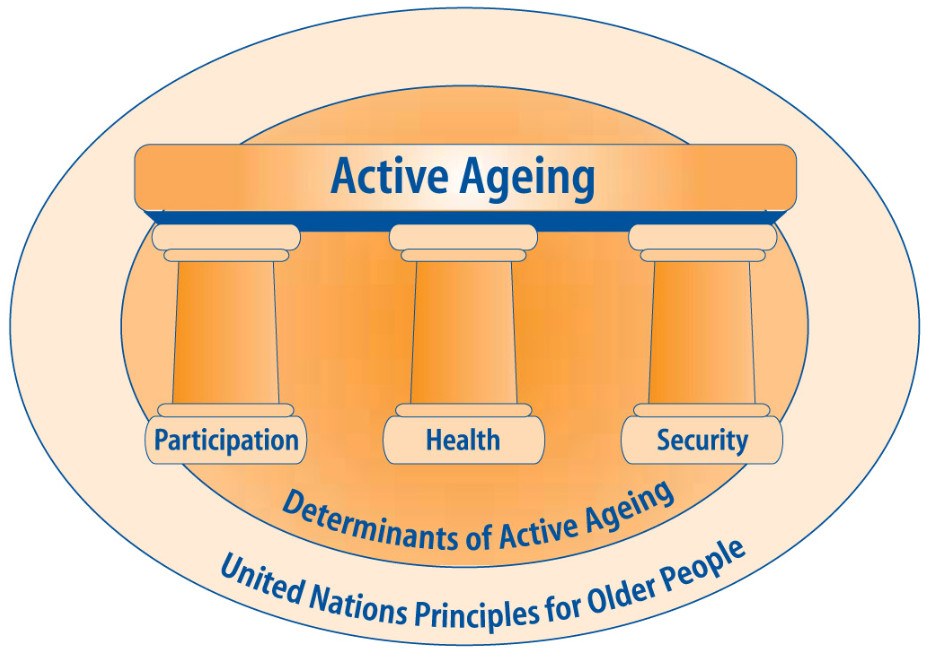

Health, participation and security are described as the three pillars of active ageing (see illustration below). Promoting them requires international, national, regional and local action.

The Three Pillars of a Policy Framework for Active Ageing

(World Health Organisation, 2002, p. 45)

Click on the image to open full size in a new window

To find out more about policies to promote wellbeing in later life, watch this interview with Dr. John Beard, Director of the Department of Ageing and Life Course at the World Health Organisation, in May 2015

Under the Care Act 2014 (s.1) ‘local authorities must promote wellbeing when carrying out any of their care and support functions in respect of a person’. This may sometimes be referred to as ‘the wellbeing principle’ because it is a guiding principle that puts wellbeing at the heart of care and support (DH, 2016, 1.2).

The Statutory Guidance to the Care Act describes ‘wellbeing’ as a broad concept which relates to the following areas in particular:

- personal dignity (including treatment of the individual with respect)

- physical and mental health and emotional wellbeing

- protection from abuse and neglect

- control by the individual over day-to-day life (including over care and support provided and the way it is provided)

- participation in work, education, training or recreation

- social and economic wellbeing

- domestic, family and personal

- suitability of living accommodation

- the individual’s contribution to society

These individual aspects of wellbeing are set out in the Care Act as the ones that are most relevant to people with care and support needs and carers. The guidance emphasises that there is no hierarchy, so all should be considered of equal importance when considering ‘wellbeing’ in the round (DH, 2016, 1.5-1.6).

b) ageing in place

Madge and Don have a long attachment to their home and local community. Like many older people, they are ageing in place and experiencing home and community as sources of support, purpose and identity. The idea of ageing in place underpins UK health and social care policy for older people, as a way of promoting independence, social participation, health and wellbeing. It is also seen as a less expensive alternative to residential care (Sixsmith and Sixsmith, 2008). However, not all older people want to remain at home and others are effectively unable to remain at home. There are also risks in staying put, especially for frail older people, including isolation, boredom, loneliness and the costs and challenges of adapting the home environment for disabled living (Hillcoat-Nalletamby and Ogg, 2014).

Successful ageing in place requires developments across a wide range of policy areas, including transport and the built environment. To find out more about what is needed, read this blog article by Victoria Pinoncely from the Royal Town Planning Institute

References

- Department of Health (DH) (2016) Care and Support: Statutory Guidance Issued under the Care Act 2014 (Chapter 1: Promoting Wellbeing).

- Hillcoat-Nalletamby, S. and Ogg, J. (2014) ‘Moving beyond ‘ageing in place’ – older people’s dislikes about their home and neighbourhood environments as a motive for wishing to move’, Ageing and Society, 34(10):1771-1796

- Sixsmith, A. and Sixsmith, J. (2008) ‘Ageing in Place in the United Kingdom’, Ageing International, 32(3):219–235

- World Health Organisation (2002). Active ageing: a policy framework, Geneva: WHO.

Knowledge, Evidence and Good Practice

a) Support networks and ageing

Madge and Don have close links with friends and other social networks. Some links were forged during their working lives, others since their retirement. Research evidence confirms that social networks are strongly associated with wellbeing in later life, but also points to differences in the role of social networks between early and later old age. As people age increasing impairment may reduce social participation and networks contract, as friends die or move away (Litwin and Stoeckel, 2013).

As the Coopers move into late old age, their wellbeing may decline as their access to social networks reduces. Targeted support, such as help with transport or befriending services, may be needed to prevent social isolation. Identifying key relationships is also important because, as energy declines, maintaining a few highly valued relationships may be less demanding and more satisfying than investing in wider friendship networks. Longitudinal research indicates that multiple and inter-related factors affect the relationship between the extent and quality of social networks and how these impact on wellbeing as people move from early to late old age (Berg et al., 2009).

Adult children are an important source of friendship and support for many older people. As a childless couple, Madge and Don are likely to be at greater risk than ageing parents of isolation and lack of support as frailty increases. Although there is evidence that childless people are likely to compensate by developing closer relationships with friends and other family, people without children are more likely to enter residential care in late life (Wenger, 2009; Schnettler and Wohler, 2015).

b) Gender and ageing

The experience of ageing, as earlier in the life course, is gendered. Don and Madge spend their time in different ways and there is evidence to suggest that the kinds of activities that promote wellbeing for men and women are different. For example, more solitary activities appear to promote wellbeing in men, whilst women fare better with social activity (Adams et al, 2011). As social isolation and loneliness, factors associated with poor physical and mental health, are more prevalent amongst older men, there has been a move towards activity based interventions, intended to promote the health and wellbeing of socially isolated older men. There is growing evidence of a beneficial impact on the health and wellbeing of older men from initiatives such as Men’s Sheds in Australia, but this is not yet conclusive. (Milligan et al, 2016)

c) Religion, spirituality and ageing

Don and Madge attend the local Methodist church. There is increasing research evidence that religion and/or spirituality contribute to health and wellbeing in old age. Various mechanisms may account for this. Religious/spiritual practices may prevent or moderate risky behaviour such as alcohol misuse and provide a sense of meaning and purpose in life which counteracts anxiety and depression. Religious/spiritual communities are also a source of social support (George et al., 2013).

Whilst church membership has been in decline in the UK, a small but growing body of research suggests that religious/spiritual beliefs and practice remain important for many older people and in particular for older people from minority ethnic groupings and faith traditions (Sadler et al., 2013). The potential contribution of religious/spiritual communities is highlighted in the Statutory Guidance to the Care Act 2014. Local authorities are advised to consider the ways a person’s cultural and spiritual networks can support them in meeting needs and building strengths, and to explore this with the person in any assessment (DH, 2016: 6.64).

References

- Adams, K.B., Leibbrandt, S. and Moon, H. (2011) ‘A critical review of the literature on social and leisure activity and wellbeing in later life’, Ageing and Society, 31(4):683-712

- Berg, A.I., Hoffman, L., Hassing, L.B., McClearn, G.E. and Johansson, B. (2009) ‘What matters, and what matters most, for change in life satisfaction in the oldest-old? A study over 6 years among individuals 80+’, Aging and Mental Health, 13(2):191–201

- Department of Health (DH) (2016) Care and Support: Statutory Guidance Issued under the Care Act 2014, March 2016, available at

- George, L K; Kinghorn, W A; Koenig, H G; Gammon, P and Blazer, D G (2013) ‘Why Gerontologists Should Care About Empirical Research on Religion and Health: Transdisciplinary Perspectives’, The Gerontologist, 53(6):898-906

- Litwin, H. and Stoeckel, K. (2013) ‘Social networks and subjective wellbeing among older Europeans – does age make a difference?’, Ageing and Society, 33(7):1263-1281

- Milligan, C., Neary, D., Payne, S., Hanratty, B., Irwin, P. and Dowrick, C. (2016) ‘Older men and social activity: a scoping review of Men’s Sheds and other gendered interventions’, Ageing and Society, 36(5): 895-923

- Nelson-Becker, H and Canda, E R (2008) ‘Spirituality, religion and aging research in social work: state of the art and future possibilities’, Journal of Religion, Spirituality & Aging, 20(3):177-93

- Sadler, E; Biggs, S and Glaser, K (2013) ‘Spiritual perspectives of Black Caribbean and White British older adults: development of a spiritual typology in later life’, Ageing and Society, 33(3):511-38.

- Schnettler, S. and Wohler, T. (2015) ‘No children in later life, but more and better friends? Substitution mechanisms in the personal and support networks of parents and the childless in Germany’, Ageing and Society, First View, Published online: 09 June 2015. DOI.

- Wenger, C. (2009) ‘Childlessness at the end of life: evidence from rural Wales’, Ageing and Society, 29(8):1243-1259.

Skills

Biographical information about Madge and Don is an essential resource for any practitioner who works with them to identify their care and support needs and to develop an appropriate response that supports their independence and wellbeing. Critically, for social work, it brings into focus the links between the individual, their health and wellbeing and their need for relationships and connection with their families, community and wider society (Knowledge and Skills Statement for Social Workers in Adult Services, DH, 2015). An understanding of what really matters to individuals and of how they live their lives is essential to ensure that care and support is tailored to their preferences and supports, their strategies and ways of coping (Tanner, 2007).

Gathering biographical and background information employs a range of skills. These include listening; asking good questions; weighing and sifting information; demonstrating understanding and empathy, showing interest in and respect for the person in their social and cultural context. Listening to an older person’s story, the information it contains and the way in which it is presented will yield invaluable insights into strengths and resources and pointers to how current difficulties might be addressed (Richards, 2000).

References

- Department of Health (DH) (2015) Knowledge and Skills Statement for Social Workers in Adult Services.

- Richards, S. (2000) Bridging the Divide: Elders and the Assessment Process, British Journal of Social Work 30(1):37-49

- Tanner, D. (2007) ‘Starting with Lives: Supporting Older People’s Strategies and Ways of Coping’, Journal of Social Work, 7(1):7-30

Activities

Housing

Housing plays an important part in active ageing and ageing in place. Do you know what your local authority is doing to meet the need for older people’s housing? If not go to their website and see what you can find. Here are some questions to guide your search:

Is there a mix of property to rent and property to buy?

Is the existing property designed for people with mild or moderate care/support needs or for people with high needs?

Is it designed for people with dementia?

When you have finished, click on this case study of councils that have been proactive in meeting the need for older people’s housing, produced by the Planning Advisory Service.

How do these approaches compare with what is happening in your area?

Assessment

When you do an assessment with an older person and/or carer do you explore the ways in which their cultural and spiritual networks can support them in meeting needs and building strengths?

How do you approach this?

What have you learnt from this experience?

or,

if you have not yet tried incorporating a cultural and spiritual dimension into your assessment:

Why not? Are there particular challenges for developing your practice in this way?

What might help you to develop confidence in this area?

Key Information

Identify an older person you know well, a friend or a relative. What key information about their personality, interests, cultural background and life story do you think would help a social worker to work with them in a person-centred way?

In your practice, how do you ensure that you have this key information about the older people you work with?

Self reflection

Make yourself comfortable. Take a piece of paper and a pencil and write your thoughts about old age for at least six minutes.

You may find it helpful to follow these suggestions for a Six Minutes Write

- Write whatever is in your head, uncensored.

- Write without stopping for at least six minutes

- Don’t stop to think or be critical, however disconnected it might seem.

- Allow it to flow with no thought for spelling, grammar, proper form.

- Give yourself permission to write anything. You do not even have to reread it.

- Whatever you write will be right: it is yours, and anyway no one else need read it.

(Bolton, G. 2010, Reflective Practice: Writing and Professional Development (3rd edition), London: Sage, p. 108)

When you have finished, re-read it if you wish.

Is there anything you have written that surprises you?

Is there anything you have written that may be significant for your practice with older people?

Additional Resources

The Coopers are a straight couple living in a market town.

The New Dynamics of Ageing Programme has produced helpful summaries from research into particular groups of older people. These include findings on:

- promoting independence and social engagement among older people in disadvantaged urban communities

- the wellbeing and participation of older people, including LGBT older people, in rural areas

- the lived experiences, social networks and family lives of older people from South Asian communities in England.

For further information about:

- Staying Put. Age UK has some useful practical tips for older people wanting to remain in their own homes.

- Ageing without children. Ageing without Children is a new initiative which aims to help people ageing without children live a later life free of the fear of ageing alone and being without support.

- Older men and mental health. The Mental Health Foundation has useful information and resources for working with older men.

- Recent examples of UK Government policy initiatives relating to older people.

Additional resources added in 2019:

- The impact of ageism on older people.

- Measuring outcomes for individuals in key areas relating to later life.

- Different attitudes about ageing across socio-economic groups.

- Active ageing and the built environment.

- Diversity in older age – Minority religions; Gypsies and Travellers; Older offenders; Older Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual people and older Transgender people; Disability; Older Refugees and Asylum Seekers; Older homelessness